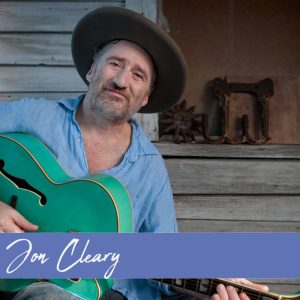

Jon Cleary

Sunday, August 5 at 2:30 p.m.

RBF Main Stage

With the release of GoGo Juice on FHQ Records, New Orleans funk master Jon Cleary returns to writing and recording the original material that has brought him critical acclaim since his 1999 album Moonburn.

Beyond Cleary’s considerable skills as a tunesmith he is equally renowned around the globe as an accomplished keyboardist and guitarist, and a deeply soulful vocalist. Cleary’s thirty-five years of intensive hands-on work on the Crescent City scene has made him a respected peer of such New Orleans R&B icons as Dr. John and Allen Toussaint. Toussaint, in fact, took time from his busy schedule to write most of the horn arrangements for GoGo Juice – thus bringing symmetry to Cleary’s recording of an entire album of Toussaint songs, entitled Occapella, which garnered rave reviews in 2012.

In addition to the Toussaint touch, GoGo Juice bursts, full flavor, with expert accompaniment by some of New Orleans’ top session men – including guitarist Shane Theriot, fellow keyboardist and vocalist Nigel Hall, and the Dirty Dozen horns – along with members of Cleary’s band, the Absolute Monster Gentlemen. (In praise of Cleary’s chemistry with this latter group, the eminent music journalist David Fricke of Rolling Stone declared that “Cleary can be an absolute monster on his own, but Cleary’s full combo R&B is as broad, deep and roiling as the Mississippi River, the combined swinging product of local keyboard tradition, Cleary’s vocal-songwriting flair for moody Seventies soul and the spunky-Meters roll of his Gentlemen”). Grammy Award-winning producer John Porter comes to GoGo Juice with a distinguished resume that includes work with the diverse likes of Elvis Costello, Carlos Santana and B. B. King, to name just a few.

Such diversity similarly characterizes the essence of Jon Cleary’s work and career. While thoroughly steeped in the classic Crescent City keyboard canon – from Jelly Roll Morton to Fats Domino to Art Neville, James Booker, and beyond – Cleary uses that century’s worth of pianistic brilliance as a point of departure to forge his own unique and eclectic style. As heard in the widely varied grooves and textures of GoGo Juice, Cleary’s sound incorporates such far-flung influences as ‘70s soul, gospel music, funk, Afro-Caribbean (and especially Afro-Cuban) rhythms and more. “I love New Orleans R&B, “ Cleary explains. “I’m a student of it – and a fan, first and foremost. But there’s little point in just going back and re-recording the old songs – although on my live solo shows, especially in New Orleans, I make a point of trying to keep the fast- disappearing tradition of the R&B pianist/singer alive by playing the old songs that are in danger of being forgotten. As for recording, however, I think the greatest New Orleans R&B records are the ones that built on what went before but also added something new. By writing new songs you get to channel all the music you absorb through your own individual set of filters – and the fun is in seeing what emerges.”

Cleary has gloriously achieved this desired synthesis of tradition-rooted originality and forward thinking on GoGo Juice. From the ska-inflected “Pump It Up” to the life-affirming Fellini-esque “second line” that is “Boneyard,” from the introspective confessional ballad “Step Into My Life” to the rambunctious funk of “Getcha GoGo Juice,” from the exquisitely unhurried syncopation of “Love On One Condition” to the pulsing Southern-soul feel of “Beg, Steal or Borrow,” GoGo Juice makes a deep personal statement by Cleary and shimmers as a multi-faceted jewel of variegated grooves.

Besides the great musicianship displayed by all who play on this album, Cleary’s songwriting similarly shines. The joyous “Getcha GoGo Juice” – “comprised entirely of lines I’ve overheard people say in New Orleans” – revels in such idiosyncratic, pithy gems of Crescent City argot as “you don’t need a license til you get caught” and “I don’t need the money, just the people I owe”. In drawing on this rich resource, Cleary followed the advice of the great New Orleans songwriter Earl King to “keep a little notepad and always jot down the trash-talking you hear on the street.” “9 to 5,” a condemnation of shallow materialism, is also based on New Orleans street language, and its title is based on a line from the traditional songs “Junker Blues” and “Junco Partner” — “Six months ain’t no sentence, and one year ain’t no time, they got boys in penitentiary doing nine to ninety-nine”:

All the beautiful people in my cable TV

They’re looking through the screen and smiling at me

And it’s all cool and lovely

In that video world

Sunsets and islands

Diamonds and pearls

Meanwhile

9-5 sho feel like 9-99

Hand to mouth

Ain’t nothing but marking time

On a related note “Brother I’m Hungry” examines the harshly contrasting proximity of wealth and poverty, from the compassionate perspective of “there but for the grace of god go I”:

We guard our jealous fortune

We got our slice of pie

Now this all begs the question

How long ‘til you and I

Might find ourselves in the same situation

How long before we all got to cry…

On a lighter note, in view of such grim realities, “Boneyard” encourages us all to enjoy life while we can:

Before I’m nuttin’ but rag and bones

Gonna gather no moss like a rolling stone

Before I make it to the boneyard

I’m gonna have my fun…

And “Bringing Back The Home” reveals Cleary’s deep love for, and understanding of, his adopted home since 1980 and references the plight of the estimated hundred thousand New Orleanians that fled Hurricane Katrina and who ten years later have yet to return:

Bringing back the home

Of the greatest gift that

America gave the world

Jazz, funk, rhythm and blues, and soul

Buddy Bolden blow your horn

It’s time to call your children home

A new wind is blowing through us all

Like driftwood washed up on the shore

Of a strange foreign land

Tired, broke, got nowhere to turn

If nobody minds the store

Lord have mercy on the 504

Jon Cleary’s love and affinity for New Orleans music goes back to the rural British village of Cranbrook, Kent, where he was raised in a musical family. Cleary’s maternal grandparents performed under the respective stage names Sweet Dolly Daydream and Frank Neville, ‘The Little Fellow With The Educated Feet’ – she as a singer, and he as a tap dancer. His father was a 50’s skiffle man and taught him the rudiments as soon as he was big enough to reach around the neck of his guitar. Upon attaining double-digit age Cleary became avidly interested in funk-filled music, buying records and intently studying their labels and album covers in order to glean as much information as possible. Such perusal revealed that three songs he especially loved — LaBelle’s “Lady Marmalade,” Robert Palmer’s version of“Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley” and Frankie Miller’s rendition of “Brickyard Blues” – were attributed to Allen Toussaint as either the songwriter, the producer, or both. Cleary’s knowledge expanded significantly when his Uncle, musician Johnny Johnson returned from a sojourn in New Orleans in the early 70’s and brought back two suitcases of rare and obscure local 45s, which allowed the adolescent Cleary to pursue his study of R&B in great depth, with special attention to the New Orleans sound that increasingly captivated him.

As soon as he was old enough to leave school in 1980 Cleary took off for the Crescent City. When his flight touched down a taxi took him straight to the Maple Leaf, a funky Uptown bar which then featured such New Orleans piano legends as Roosevelt Sykes and James Booker. Cleary got a job painting the club, and lived a few doors down for a time, allowing him unlimited free access to all the great New Orleans music performed within. One night when James Booker didn’t show up, the club’s manager insisted that Jon get up and play before the paying customers demanded a refund. Thrust suddenly into the spotlight Jon was ready, willing and able to play his first paying gig in New Orleans – and although he had come to town as a guitarist, this debut was also the first step of his career as a pianist.

Soon Cleary reached the existential crossroads of either devoting his life to the city’s music, or returning to England. Cleary chose New Orleans, and before long he began to land sideman gigs with the venerable likes of such New Orleans R&B legends (and his childhood heroes) as guitarists Snooks Eaglin, and Earl “Trick Bag” King, and singers Johnny Adams, and Jessie Hill.

By 1989, Cleary had recorded his first album of eight including the new GoGo Juice. His increasingly high-profile performances revealed a level of proficient versatility that led to recording sessions and international touring work – in an appropriately wide stylistic range – in the bands of Taj Mahal, John Scofield, Dr. John and, most notably, Bonnie Raitt. As a songwriter, he has written and co-written songs with and for Bonnie Raitt and Taj Mahal and the decade that he spent working with Raitt inspired her to unabashedly dub Cleary “the ninth wonder of the world.”

Jon Cleary left Bonnie Raitt’s band in 2009 to concentrate on his own music. And now, 35 years since he arrived in New Orleans, Cleary has made an eloquent, definitive and future-classic artistic statement. “Funk is the ethnic folk music of New Orleans,” Cleary says, “and I wanted to infuse GoGo Juice with a sound that was true to the city I love. It’s the kind of record that could only be made in New Orleans.”

Biography courtesy http://www.joncleary.com/